paeony

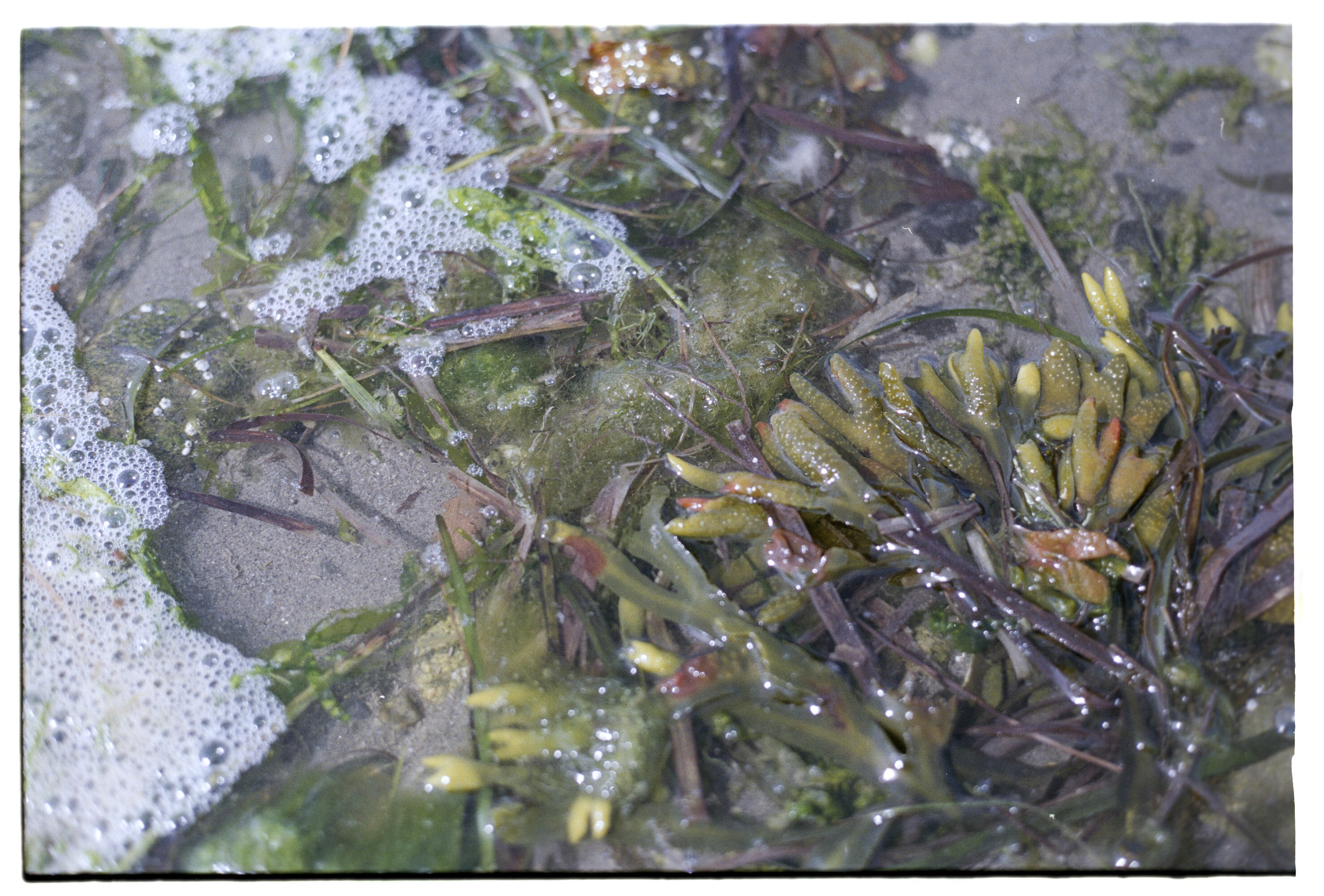

mystic beach

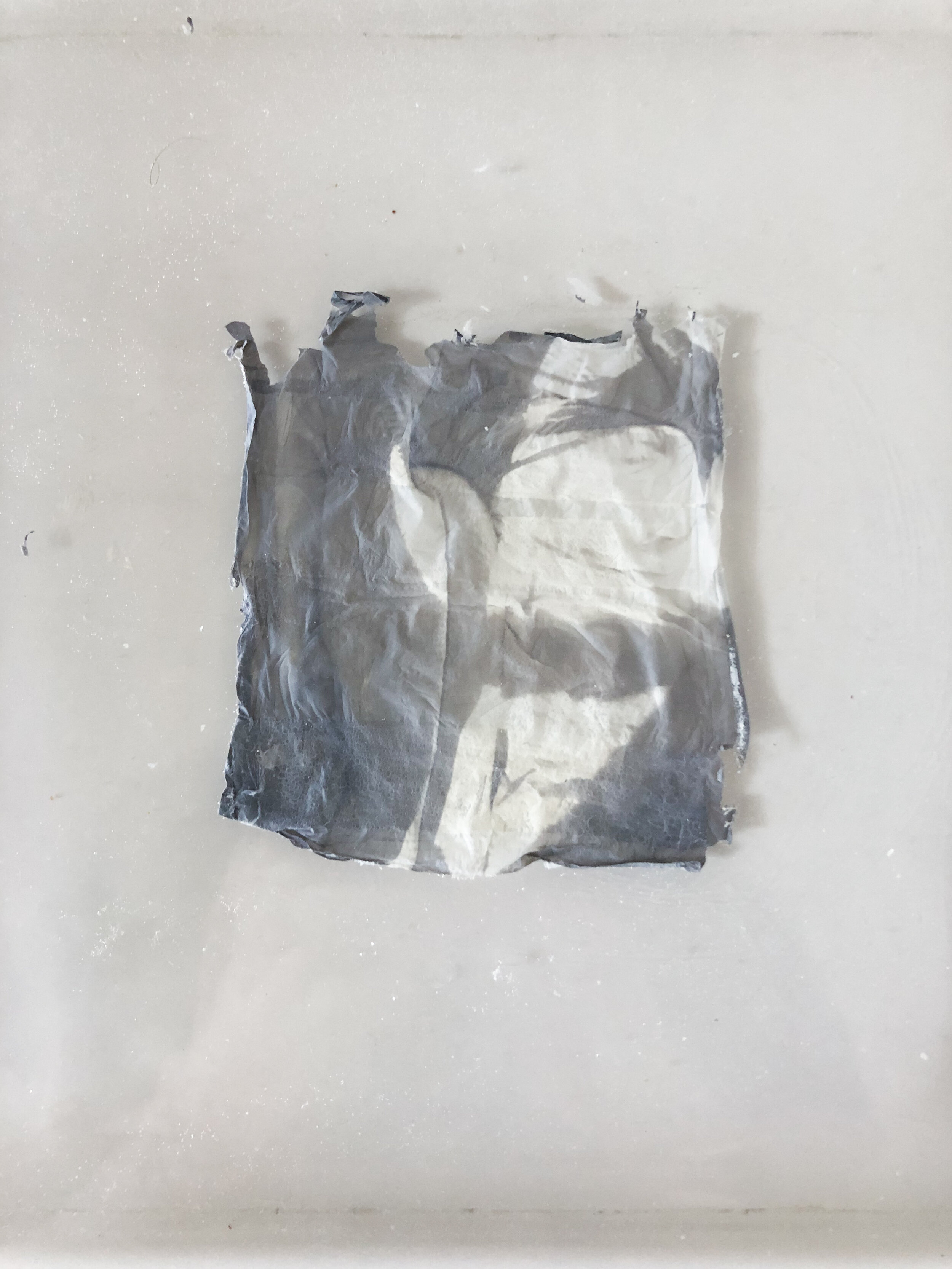

untitled (in spirit): work in progress

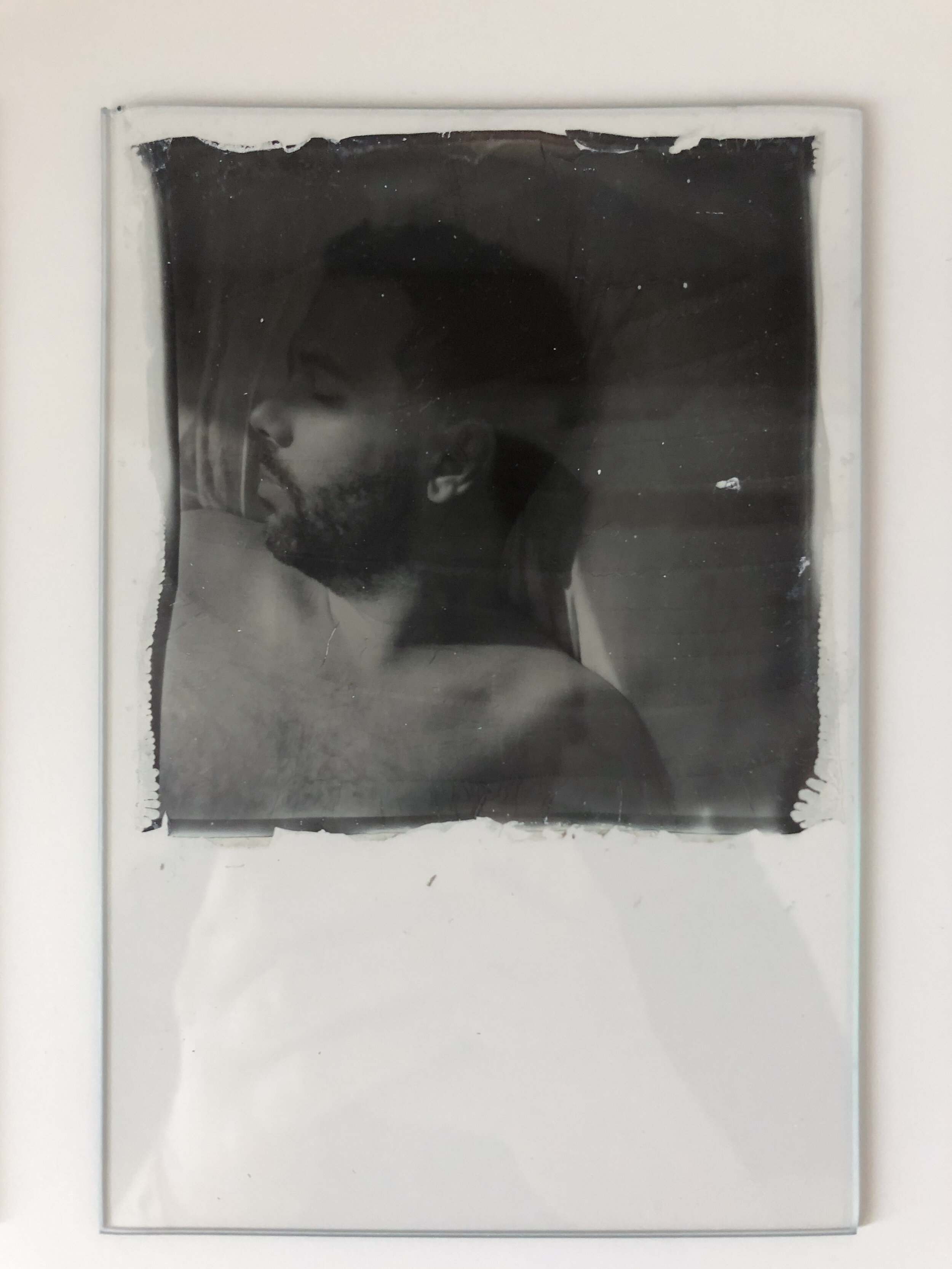

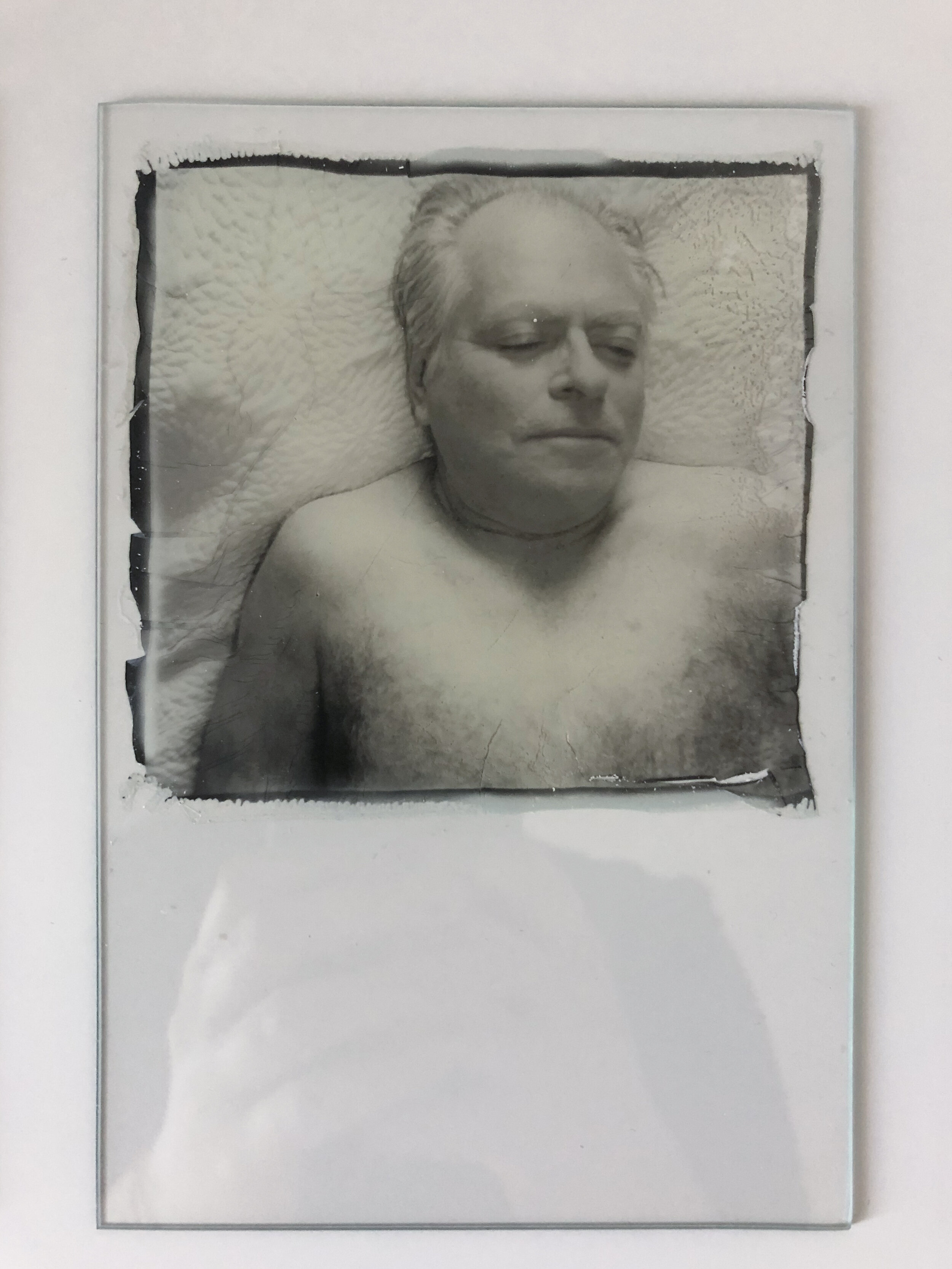

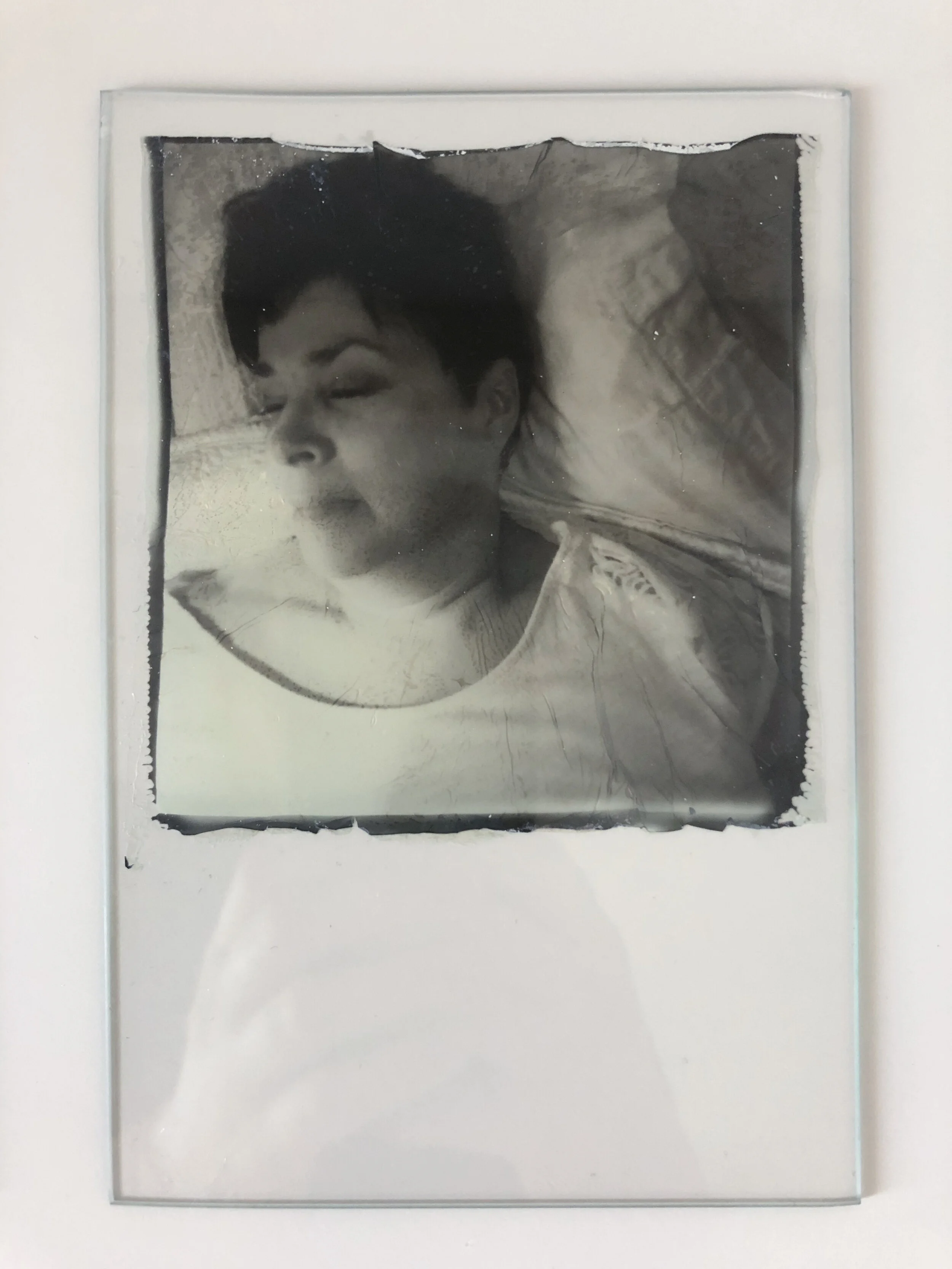

Untitled (In Spirit)

The history of photography is riddled with hauntings. In Victorian times, when the invention of photography had become stable, portraits were often done of the deceased, as they were the ones thought of as important enough to keep images of (as it was quite costly). But cameras were thought to capture more than just facsimiles; they were thought to capture the souls of sitters as well. This project aims to both be a visual nod to the history of photography, as well as an active mode of participatory art in spirit photography.

Spirit photography was discovered in 1861 by photographer William H. Mumler after his self portraits contained something, or someone, extra. The image he produced in his studio, alone, also contained (by many accounts) the image of his deceased cousin. Photography at this time had become more accessible since the invention of the Daguerreotype in 1839, and it was viewed as something that captured the absolute truth. The idea that a photograph could capture more than what was in the room, and specifically spirits from the other side, came at a time in American history, the Civil War, when people found comfort in capturing the spirits of their lost loved ones. But there was also a question of truth. In Louis Kaplan’s “Where the Paranoid Meets the Paranormal: Speculations on Spirit Photography”, he discusses the feeling of paranoia that surrounded the spirit photograph in the 19th century:

“The discourse of spirit photography revolves around such paranoid questions as ‘Are we seeing the truth?’ or more complexly, ‘Can such a truth be seen at all?’ The believers assert that paranormal photography provides access to a ‘spiritual truth’ beyond the normal powers of perception. That is why Mumler begins his memoirs: ‘In these days of earnest inquiry for spiritual truths, I feels that it is incumbent upon me to contribute what evidence of a future existence I may have obtained in my fourteen years’ experience with Spirit-Photography’. The paranormal photograph confronts the viewer with this paranoid question: ‘Am I really seeing a spiritual truth?’”.

This question of spiritual truth is what can still haunt the images captured from this time, and something we still struggle with today, is such a truth possibly accessible?

Another aspect to consider during this time, (in the 1870’s) was the mortality rate, especially in youth, which raised significantly due to both cholera and tuberculosis outbreaks. The shift from fearing the photograph, and what it could capture, switched to a far more common use of the photograph in post-mortem photography, to preserve the loved one forever. In Nancy M. West’s “Camera Fiends: Early Photography, Death, And The Supernatural” she describes how, much like our “contemporary mortician, the nineteenth-century photographer transformed the dead into the almost living”, in this way we can understand the need of post mortem photography as it could act as a means to grieve while simultaneously keeping the loved one alive.

The project entitled: Untitled (In Spirit), uses both of these Victorian ideas, of spirit photography and post-mortem photography. The series of photo objects aims to confront and capture the viewer in a delicate haunting dance. The idea is to not only to capture a person within a standard portrait, but to place the viewer, and their ideas of the person within the portrait, into the frame as well. This will act, in a way, as a “spirit photograph”, but will also act as a way to position the viewer as an active conductor in the narrative of the portrait’s figure. In this way each physical photograph carries with it the stories and “souls” of each viewer, as they project their narratives to the portraits.

The sitters, or ‘sleepers’ are posed in a sleep-like state, as a way to inhabit a space that is both living and dead, this way the viewer can conjure up and project more haunted narratives to the portraits. The images are created through a process of lifting polaroid emulsions onto glass, which is a delicate process and also produce delicate and fragile pieces. The emulsions carry with them their own personalities; they are delicate, ethereal, and tissue like membranes of one-of-a-kind images. This too adds to the importance of the material as they reflect the nature of antique images that have survived over the centuries. The series has begun with my personal loved ones, much like the aforementioned post-mortem photographs, to keep them in a delicate limbo, but the series will grow to capture more sleepers in order to have a varied composite of those who have been loved, and will be lost, much like the remnants of antique photographs that can still be found and cherished by strangers.

Bibliography

Borgo, Melania, Marta Licata, and Silvia Iorio. “Post-mortem Photography: the Edge Where Life Meets Death?” in HSS, vol. V, no. 2 (2016): 103-115.

Brown, Nicola. “Empty Hands and Precious Pictures: Post-mortem Portrait Photographs of Children” in Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies, Vol. 14, No. 2 (2009).

Ferris, Alison. “Disembodied Spirits: Spirit Photography and Rachel Whiteread's ‘Ghost’” in Art Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn, 2003), pp. 44-55.

Flint, Kate. “Photographic Memory – Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net.” Érudit, Université De Montréal, 12 May 2009, www.erudit.org/fr/revues/ravon/2009-n53-ravon2916/029898ar/.

Henderson, Andrea. “Magic Mirrors: Formalist Realism in Victorian Physics and Photography” in Representations , Vol. 117, No. 1 (Winter 2012), pp. 120-150.

Kaplan, Louis. “Where the Paranoid Meets the Paranormal: Speculations on Spirit Photography” in Art Journal, Vol. 62, No. 3 (Autumn, 2003), pp. 18-29.

Sweet, Timothy. “Ghost Dance? Photography, Agency, and Authenticity In "Lame Deer, Seeker Of Visions" in Modern Fiction Studies, Vol. 40, No. 3, Autobiography, Photography, Narrative (Fall 1994), pp. 493-508.

West, Nancy M. “Camera Fiends: Early Photography, Death, And The Supernatural” in The Centennial Review, Vol. 40, No. 1 (Winter 1996), pp. 170-206.

35mm portraits

LAKE HOUSE

hands

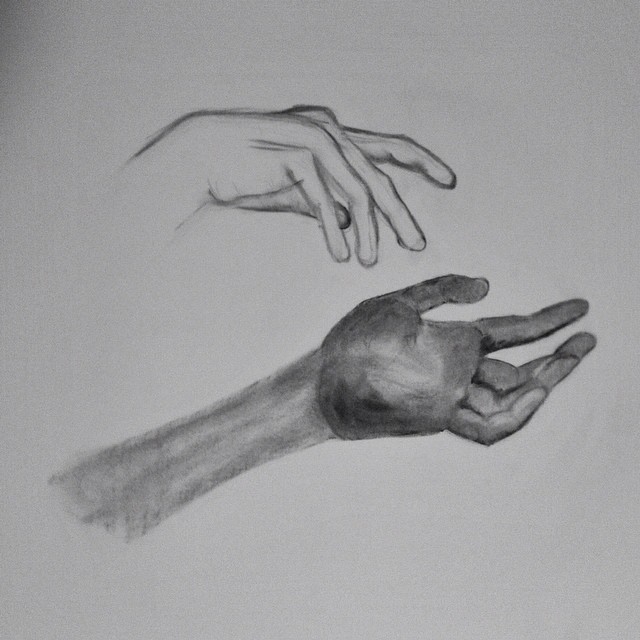

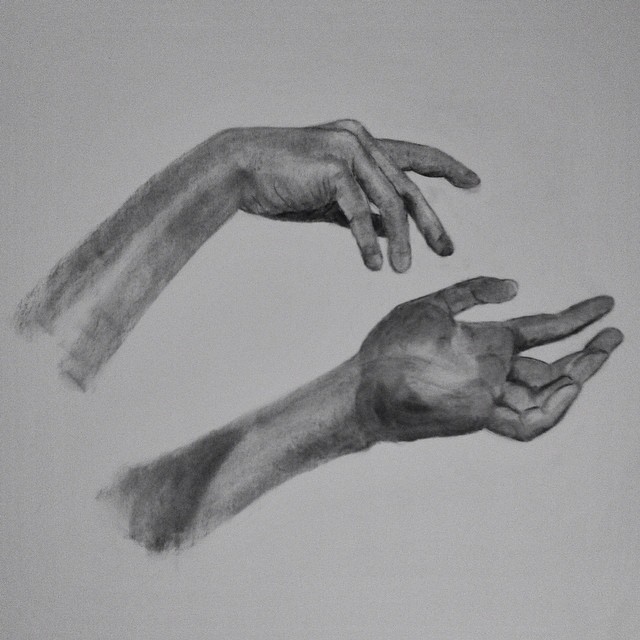

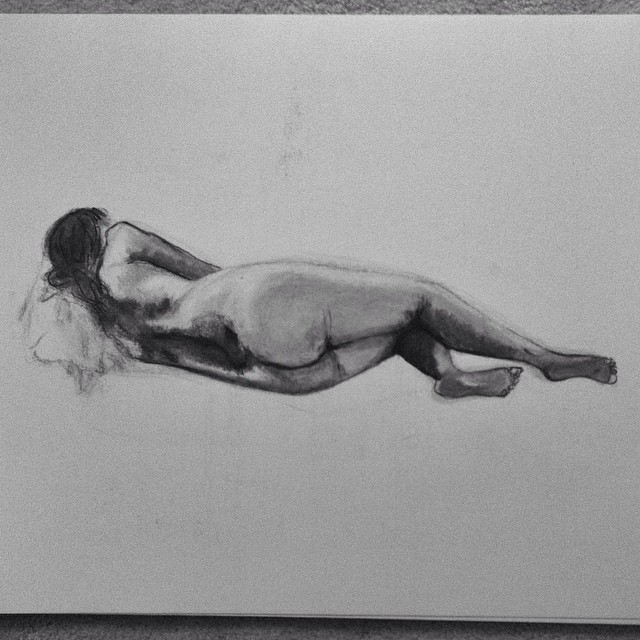

first time drawing hands: 45mins, 70mins, final